𝔍oseph Goodavage argues that other than the explosion of a star as a supernova, “there are few splendors from the hand of God or man to match the drama of a great comet flaring across the vault of heaven” (6). Catastrophes from wars to epidemics, natural disasters to famines, have been blamed on the unexpected appearance of comets in the night sky. References to these superstitions are legion in the Western canon. From John Milton’s description of Satan as “like a comet” in Paradise Lost to Shakespeare’s famed claim in Julius Caesar that “When beggars die, there are no comets seen; The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes,” the equality comet = calamity appears ubiquitous in Western culture. Even Eastern cultures, historically meticulous documenters of the coming and going of heavenly apparitions including what became known in China as “broom stars,” widely regarded comets with suspicion.

But it was in medieval Europe that clear connections were drawn between the timing of cometary apparitions –malignant violations of the immutable and perfect heavens – and mishaps and misfortune. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles feature many such correlations; for example, in the Year 729 the appearance of two comets is connected with the death of King Osric and “the holy Egbert” (Whitelock 28). But the most famous comet-linked event in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles is clearly that immortalized in the Bayeux tapestry, the connection between the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1066 and the Battle of Hastings. According to the Chronicle,

Then over all England there was seen a sign in the skies such as had never been seen before. Some said it was the star ‘comet’ which some call the long-haired star, and it first appeared on the eve of the Greater Litany, that is 24 April, and so shone all the week. (Whitelock 140)

|

| The selection in question Image from Wikimedia Commons, used for commentary |

Given this historical precedent, it is not surprising that comets as omens appear in the medievalisms of fantasy literature. In the early chapters of E.R. Eddison’s classic 1922 work, The Worm Ouroboros, Lord Gro is deeply troubled by a prescient dream of doom. A central vision is “fiery signs” in the night sky, especially a “bearded star” (27) – a comet – that seemed to herald the shedding of blood (32). More recently a red comet appears in two 1990s fantasy novel series, George R.R. Martin’s still-unfinished A Song of Ice and Fire and Andrzej Sapkowsi’s Witcher series, a coincidence significant enough to make this astronomer sit up and take notice. Martin’s ongoing novel series – A Game of Thrones (1996), A Clash of Kings (1998), A Storm of Swords (2000), A Feast of Crows (2005) and A Dance with Dragons (2011) – is the more widely known of the two, in part thanks to the now-completed hit HBO series Game of Thrones and the fact that Sapkowski’s works have only recently been published in English.

The culminating event in Martin’s first novel is the funeral pyre of the Daenerys Targareyn’s Dothraki husband, Drogo, and the hatching of her dragons. The Dothraki search the heavens for a sign of the star that was kindled by Drogo’s soul. Instead, a “comet, burning red. Bloodred; fire red” is seen, and taken as a positive portent (Martin, AGoT, 804). Daenerys follows the comet across the desert to the city of Qarth, interpreting this “shierak qiya, the Bleeding Star” as a sign sent by the gods (Martin, AGoT, 188). Throughout A Clash of Kings, characters from different cultures note the comet in the sky, and interpret it through the lens of their personal belief systems and political allegiances. For example, the Brothers of the Night Watch on the Wall name it after their commander, referring to it as “Mormont’s Torch, saying (only half in jest) that the gods must have sent it to light the old man’s way through the haunted forest” (Martin, ACoK, 97). The followers of the Drowned God believe it to be a sign from their god, with Aeron Damphair calling it evidence that “It is time to hoist our sails and go forth into the world with fire and sword” (Martin, ACoK, 179). At the same time, Melisandre proclaims that the comet is the fulfillment of an ancient prophecy heralding Stannis Baratheon as the rebirth of the hero Azor Ahai (Martin, ACoK, 39; ASoS, 349). In Riverrun the comet is said to be a “red flag of vengeance for Ned” Stark’s death at the hands of King Joffrey, as well as an “omen of victory” for the Tullys (Martin, ACoK, 117). Ser Brynden offers the most honest interpretation of all, especially given Martin’s taste for killing off his characters: “That’s blood up there, child, smeared across the sky…. Was there ever a war where only one side bled?” (Martin, ACoK, 118). Even the wise Maester Cressen, not given to belief in omens, wondered at the uncharacteristic brightness of the comet and its “terrible color, the color of blood and flame and sunsets” (Martin, ACoK, 1). Thus the interpretation of the comet is clearly in the eye of the beholder. The comet was one of a number of details (e.g. Jon Snow’s parentage) introduced and quickly abandoned by the HBO series.

On the other hand, while Andrzej Sapkowski’s novel series is completed, the Netflix adaption is only in the pandemic-delayed filming stage of Season 2. The economics-trained travelling furs salesman initially introduced his unnamed medieval world in the short story “Wiedzmin” (Witcher), which took third prize in a contest in Fantastyka, a Polish science fiction and fantasy magazine in 1986 (Purchese). Additional short stories continued to appear in the magazine until they were published as book-length collections in 1992 (Sword of Destiny [Miecz przeznaczenia] ; English translation 2015) and 1993 (The Last Wish [Ostatnie Życzenie] ; English translation 2007]). A series of five subsequent novels followed: Blood of Elves (Krew Elfów 1994; English translation 2008), The Time of Contempt (Czas Pogardy 1995; English translation 2013), Baptism of Fire (Chrzest Ognia 1996; English translation 2014), The Tower of the Swallow (Wieża Jaskółki 1997; English translation 2016), and The Lady of the Lake (Pani Jeziora 1999; English translation 2017). Season of Storms (Sezon Burz), a novel set in the same time period as The Last Wish, appeared in Polish in 2013 (English translation 2018). Until the December 20, 2019, release of the wildly popular first season of the Netflix series The Witcher, the Witcherverse was perhaps most widely known outside of Poland through the internationally successful computer games created by CD Projekt Red: The Witcher (2007), The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings (2011), and The Witcher III: The Wild Hunt (2015). In the mythology of the series, Witchers are monster hunters mutated as children using a variety of herbs, chemicals, and magic and trained in martial arts, magic, and monster physiology and taxonomy. In return they are rewarded with superhuman strength, agility, and senses, an extremely long lifespan, and resistance to disease; however, they are sterile. The adventures of the Witcher Geralt with his sorceress lover Yennifer and adoptive daughter Ciri (the eugenically engineered child of destiny) reveal that humans are the true monsters.

Sapkowski utilizes the metaphor of a comet for dramatic effect on several occasions. When a “red-hot horseshoe” is placed into a corrupt priest’s long johns he shoots “straight ahead like a comet with a smoking tail” (Sapkowski, BF, 167), while the deadly company of the Wild Hunt (disguised in the form of an ominous cloud] is repelled by Yennefer and shoots “upwards into the sky, lengthening and dragging a tail behind it like a comet’s as it sped away” (Sapkowski, TC, 100-1). Here Sapkowski draws upon a common misconception, that comets streak across the sky like meteors. This fallacy is inspired by centuries of paintings and later photographs of comets with their impressive gossamer tails breathlessly suspended as if captured midflight.

A literal comet is featured in The Lady of the Lake, a “golden and red bee of a comet” seen “crossing the sky from west to east, dragging in its wake a flickering plait of fire” (Sapkowski, LL, 207). The event was singular enough in Sapkowski’s universe to be used as an important chronology marker by Nimue, who features prominently in a “flashforward” into the future of Geralt’s world. She notes that “The red comet was visible for six days in the spring of the year the Cintran Peace was signed. To be more precise, in the first days of March” (Sapkowski, LL, 29). Nimue’s rather scientific detachment is contrasted with the reactions of characters of the comet’s time, who regard it with far more superstition. Jarre, a young scribe educated at the Temple of Melitele, privately “wondered what this strange phenomenon, mentioned in many prophecies, might actually auger” (Sapkowski, LL, 207).

Elsewhere a “seller of amulets and remedies” opines that the

red colour indicates that it’s a comet of fevers. Blood and fire, and also of the iron which springs from the fire. Dreadful, dreadful defeats will befall the people! Great pogroms and massacres will happen. As it says in the prophecy: corpses will pile up to a height of a dozen ells, wolves shall howl on the desolate ground, and men will kiss other men’s footsteps… Oh woe to us!A wily mercenary has a different interpretation, noting that their Nilfgaardian foes also see the comet above their heads, so “Why, then, should we not assume that it foretells their defeat and not ours?” (Sapkowski, LL, 221).

Yet another interpretation is held by Aarhenius Krantz, “a sage, alchemist, astronomer and astrologer” who observes this comet and its “fiery red tail” with his (anachronistic) simple telescope, intrigued because he knows that such an object “usually heralded great wars, conflagrations and massacres.” Invoking a mixture of pseudoscience and science that characterizes the Witcher series, he decides that the comet is, indeed, a portent of war, but since there is already a war in progress, he will scientifically determine the orbit of the comet so that they will know when it will return and, hence, the next war will occur (Sapkowski, LL, 259).

Such an expectation – that the appearance of a bright comet should lead to doom and gloom – has unfortunately survived the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions in some quarters. The 1910 return of Halley’s Comet generated a wave of comet-hysteria when scientists announced their unexpected discovery of deadly cyanogen in the comet’s tail – a tail that the earth would pass through. According to the May 18, 1910, issue of The New York Times, the citizens of Chicago were terrified:

Especially has the feminine portion succumbed…. ‘I have stopped [up] all the windows and doors in my flat to keep the gas out,’ said one woman over the telephone. ‘All the other women in the building think it is a good thing, and all are doing the same.’… Physicians say that there were scores of calls to-day for their services from women who were suffering from hysteria. (Flaste et al. 63)

Astronomers’ subsequent assurances that the comet’s tail was far too ethereal to pose a threat did little to calm fears (much to the delight and financial gain of charlatans who sold “comet pills,” the modern equivalent of various medieval potions) (Kronk 2011).

|

| The ruddy Comet West Image taken from Wikimedia Commons, used for commentary |

|

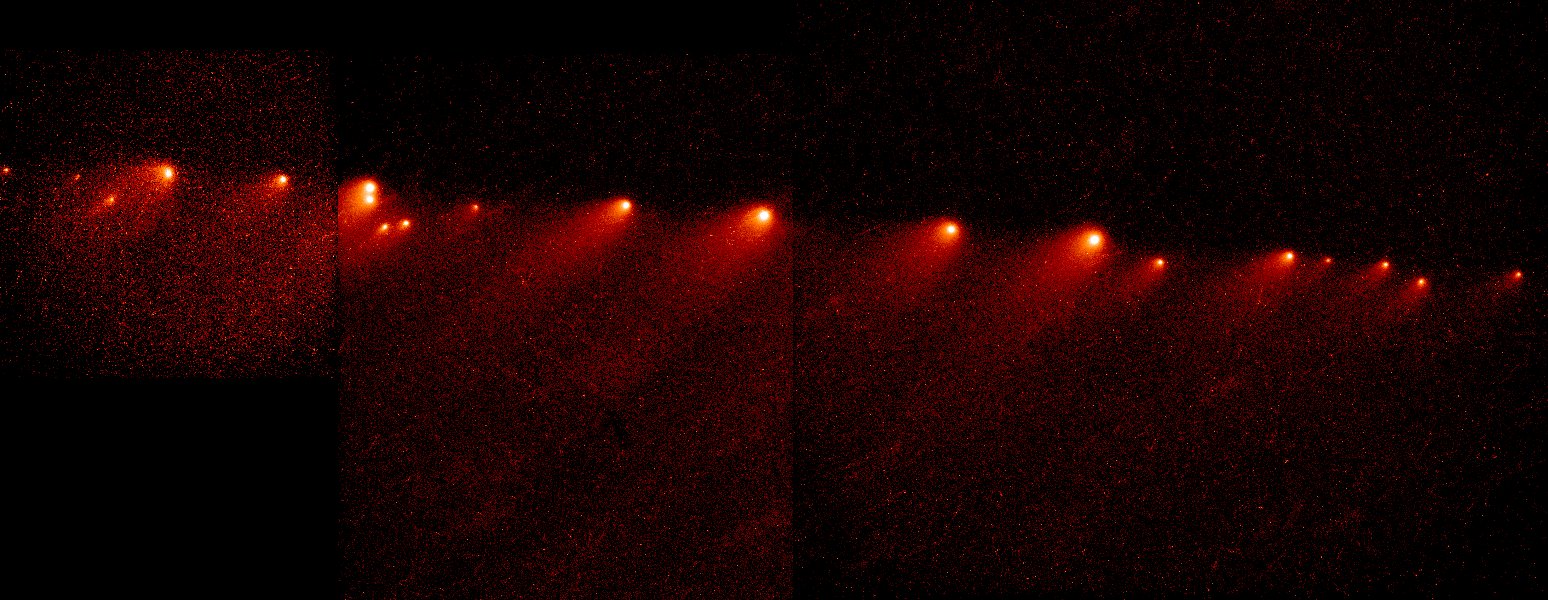

| Fragments of Shoemaker-Levy 9--red again Image from Wikimedia Commons, used for commentary |

|

| One of the "black eyes" Image taken from Wikimedia Commons, used for commentary |

On July 23, 1995, amateur astronomers Alan Hale and Thomas Bopp independently discovered a comet that, like Kohoutek before it, promised to deliver a spectacular show at closest approach in 1997, based on its unusually large size. But backyard observers did not have to wait that long for a naked-eye comet; on January 30, 1996, Japanese amateur astronomer Yuji Hyakutake discovered his second comet in five weeks. While more conservative in girth than Hale-Bopp, Comet Hyakutake’s orbit was forecast to bring it unusually close to our planet a scant two months later. Not only was it easily visible to the unaided eye from even light-polluted skies (as I can personally attest), but from dark skies, its tail stretched an impressive 100 degrees (Hale 2020). It is therefore quite possible that both Martin and Sapkowski joined millions of others amateur stargazers around the world in gaping skyward in awe. Not surprisingly, sensational false claims of an impending impact between the comet and our planet surfaced in supermarket tabloids (Kronk 2011).

|

| Hale-Bopp's worth seeing. Image taken from Wikimedia Commons, used for commentary |

|

| So's Hyakutake. Image taken from Wikimedia Commons, used for commentary |

_on_Jul_14_2020_aligned_to_comet.jpg) |

| The ruddy NEOWISE Image from Wikimedia Commons, used for commentary |

For example, Seneca described the comet of 146 BCE as “as large as the Sun. Its disc was at first red, and like fire, spreading sufficient light to dissipate the darkness of night” (Olivier 3). In 905 CE, a comet observed in China, Japan, and Europe was described as having “rays of 45 to 60 degrees and was blood-red in color” (Yeomans 387). The 1066 apparition of Halley’s Comet was also described as looking “like an eclipsed moon,” i.e. coppery red (Kronk, 1999, 77). As an adult, French surgeon Dr. Ambrose Paré recalled his boyhood observations of the comet of 1528:

This comet was so horrible, so frightful, and it produced such great terror in the vulgar that some died of fear and others fell sick. It appeared to be of excessive length and was of the color of blood. (Goodavage 17-8)One of the most meticulous naked-eye observers of all time, Tycho Brahe, described the comet of 1577 as having a tail that “appeared a reddish dark color similar to a flame seen through smoke” (Yeomans 36). More recently, Halley’s Comet terrified indigenous people in Bermuda in 1910 on the night of King Edward VII’s death due to the red color of its tail. It was declared a sign of the end of the world and impending war (Flaste et al. 75). Well-known popularizer of astronomy Mary Proctor herself noted an uncharacteristic red hue in the normally yellow planet Venus at the same time (as well as a ruddy crescent moon), and ascribed the red color of all three objects to their light passing “through the mist, low down on the horizon” (“Comet’s Red Glare”). Other atmospheric effects can also explain an unusual red tint in a comet. For example, noted visual observer Stephen O’Meara ascribed the reddish tint in his July 2020 image taken from Botswana of the aforementioned Comet NEOWISE to “wind-blown dust in Earth’s atmosphere” (Irizarry). Similarly, I witnessed both Venus and the brilliant star Sirius to have a reddish tint in the predawn sky in September 2020 due to the presence of ash carried from the West Coast wildfires all the way to New England.

Throughout human history, comets have been a source of fear and wonder. They have inspired individuals to create both beautiful works of the hands and mind, and wish ill upon and commit atrocities against themselves and others. It appears to matter little whether the hands and minds are medieval, modern, or immersed in medievalisms. Andrzej Sapkowski has boasted that “My vision of Fantasy is almost real. You have to believe that which occurs in the stories, because they are not a fairy tale” (Lsrry). In the case of their use of red comets in their medievalist fiction, Sapkowski (and Martin) have taught this astronomer quite a few things about what is fantasy, and what is real.

Bibliography

- Chris H. (June 12, 2002) “Eastern Cities and Peoples.” So Spake Martin https://www.westeros.org/Citadel/SSM/Month/2002/06

- Ciarán (December 13, 2013) “The Christmas Monster ‘Kohoutek’ and the Children of God.” Come Here to Me! https://comeheretome.com/2013/12/13/the-christmas-monster-kohoutek-and-the-children-of-god/

- “Comet’s Red Glare That Amazed Bermudians Easily Explained.” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 10, 1910: 2. https://www.newspapers.com/image/136435568/

- Daly, Gavin (March 24, 1996) “Astrologers Say Comet Could Change Our Lives.” Hartford Courant, https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1996-03-24-9603240200-story.html

- Eddison, E.R. (2008 [1922]) The Worm Ouroboros. London: Jonathan Cope [Forgotten Books]

- Flaste, Richard, Holcomb Noble, Walter Sullivan, and John Noble Wilford (1985) The New York Times Guide to the Return of Halley’s Comet. New York: Times Books

- Goodavage, Joseph F. (1973) The Comet Kohoutek. NY: Pinnacle Books

- Gorman, Christine (February 1, 2016) “The Comet that Battered Jupiter, and Shook Congress.” Scientific American https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/s19-the-comet-that-battered-jupiter-and-shook-congress/

- Hale, Alan (1997) “Hale-Bopp Comet Madness.” Skeptical Inquirer 21.1: 25-28

- Hale, Alan (March 21, 2020) “Comet of the Week: Hyakutake C/1996B2.” RocketSTEM, https://www.rocketstem.org/2020/03/21/ice-and-stone-comet-of-week-13/

- Howell, Elizabeth (March 15, 2013) “Why You’ll Never See a Red Comet Like in ‘Game of Thrones’.” Universe Today, https://www.universetoday.com/100665/why-youll-never-see-a-red-comet-like-in-game-of-thrones/

- Irizarry, Eddie (July 27, 2020) “How to see Comet NEOWISE.” EarthSky, https://earthsky.org/space/how-to-see-comet-c2020-f3-neowise

- Kronk, Gary W. (June 8, 2011) “Comet Hysteria and the Millennium: A Commentary.” Yowcrooks, https://yowcrooks.wordpress.com/2011/06/08/comet-hysteria-and-the-millennium-a-commentary-by-gary-w-kronk/

- Kronk, Gary W. (1999) Cometography, volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Levy, David, Eugene M. Shoemaker, and Carolyn S. Shoemaker (1995) “Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 Meets Jupiter.” Scientific American 273.2: 84-91

- Lssry (July 27, 2008) “Part 1 of the June 2008 Fantasymundo Interview with Andrzej Sapkowski.” OF Blog. Retrieved from http://ofblog.blogspot.com/2008/07/part-i-of-june-2008-fantasymundo.html

- Martin, G.R.R. (2011) A Clash of Kings. New York, NY: Bantam Books

- Martin, G.R.R. (2011) A Game of Thrones. New York, NY: Bantam Books

- Martin, G.R.R. (2011) A Storm of Swords. New York, NY: Bantam Books

- Olivier, Charles P. (1930) Comets. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Company

- Plait, Phil (July 21, 2020) “Comet NEOWISE goes from red to green and has spiral arms.” Bad Astronomy, https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/comet-neowise-goes-from-red-to-green-and-has-spiral-arms

- Robinson, B.A. (Sept 22, 2009) Heaven’s Gate: Christian/UFO Believers.” Religious Tolerance, http://www.religioustolerance.org/dc_highe.htm

- Whitelock, Dorothy (ed.) (1961) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode Yeomans, Donald K. (1991) Comets. New York: John Wiley and Sons

The Tales after Tolkien Society welcomes contributions to the blog from members and from interested parties. Please send yours to talesaftertolkien@gmail.com, and thank you!

No comments:

Post a Comment