Read the next entry in this series here.

“The Ice Dragon”

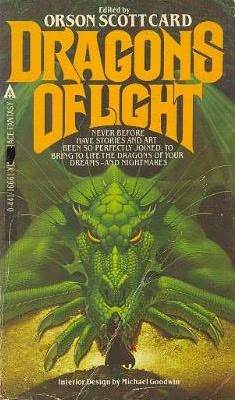

Orson Scott Card’s Dragons

of Light, 1980

“The Ice Dragon” is

frequently mistaken for an A Song of Ice and Fire story, and the reasons

for that mistake are clear. The setting and thematic material are very similar

to A Song of Ice and Fire, even if closer reading reveals that this is

not Westeros and these are not the Targaryen dragons.

In this unnamed land,

two kings—one north, one south—are at war, and appear to have been for years,

if not decades. Both sides have dragons as well as ground-based armies, and

Adara’s uncle, Hal, is a dragonrider in service of the southern king. Adara has

a special relationship with winter; she was born in the dead of the worst

winter in living memory, her skin is cold to the touch, and she’s friends with

the ice dragon that accompanies winter every year. This isn’t the Game of

Thrones wight-dragon that breathes fire/ice that Viserion turns into, but a

true dragon made of ice that breathes cold and chills everything around it.

There are also ice lizards, which only Adara can play with because her hands

aren’t as hot as everyone else’s, so she doesn’t kill them just by handling

them.

~*~

Ice formed when it

breathed. Warmth fled. Fires guttered and went out, shriven by the chill. Trees

froze through to their slow secret souls, and their limbs turned brittle and

cracked from their own weight. Animals turned blue and whimpered and died,

their eyes bulging and their skin covered with frost.

~*~

“The Ice Dragon” reads

very much like practice for A Song of Ice and Fire, with

not-insignificant thematic similarities: dragons, winters, war, rape, and ice

vs. fire. As in ASOIAF, the dragons are weapons of mass destruction,

forces of nature barely controlled by their riders, not really characters in

their own right. Even the ice dragon is more of a prop for Adara’s story than a

character in it, a representation of winter and the thing that allows Adara to

be a hero at the end of the story. It represents her difference from everyone

else, as well, and the change she undergoes at the end of the story—becoming

warm-blooded, losing her affinity with cold and winter and growing closer to

her family—is a physical representation of her growing up after the traumatic

experience just before the end of the story. Adara’s affinity with cold also

represents her loss—her mother died when she was born, so unlike everyone else

in the story who love summer and had Beth in their lives, even if only for a

little while, Adara grows up cold, a loner, different than everyone else.

This story also sees

Martin developing his ideas about medieval warfare and the plight of the common

folk who just want to farm their land and live their lives. Hal brings them

news of how the war is going, urging them to leave when it turns bad. At the

beginning of winter, he warns them that in the spring, the opposing king is

going to break through their lines and they won’t be able to stop him. Then the

retreat begins, right past the farm, a steadily degenerating stream of men that

lasts a month; one of the last groups through robs a neighboring farm and rapes

the woman who lives there. Martin makes a point of remarking on the color of the

rapist’s uniform, which marks him as one of “their” people, not the enemy. The

enemy, when they arrive, also perpetrates horrors, nailing John to the wall and

forcing him to watch them rape Teri. Martin has a slightly disturbing habit of

assuming that rape is inevitable, that given the chance and the excuse and the

low likelihood of punishment, men will assault

women. I understand that he uses it as one of the many horrors of war and

believes that depiction of war without rape would be dishonest, but it shows up

in too many other contexts in his writing to ignore.

Adara bears striking

similarities to both Arya and Sansa. She’s young, different than everyone else,

a loner, and a bit selfish in the way little kids can be selfish. This is most

evident toward the end of the story, when John decides he’s not leaving the

farm, but he can at least save Adara by sending her with Hal. Adara refuses to

go with Hal, instead running away into the forest. Her refusal to leave costs

Hal his life. She tries to run away with the ice dragon—in the heat of

summer—but chooses to go back to save her family. The ice dragon helps, killing

the enemy dragons and riders, but it dies, too, both because it’s summer and

because it’s fighting fire-dragons. So there are really two ways of looking at

the climax of the story: Adara’s a hero, or Adara’s a thoughtless little kid

who gets her uncle and a majestic and innocent beast killed because of her

thoughtlessness. Not to mention her father’s injuries and her sister’s rape,

though it’s doubtful she would have been able to stop that even if she hadn’t

run away.

~*~

When the first frost came, all the ice lizards

came out, just as they had always done. Adara watched them with a little smile

on her face, remembering the way it had been. But she did not try to touch

them. They were cold and fragile little things, and the warmth of her hands

would hurt them.

~*~

The ending, in true

Martin fashion, is bittersweet. The family leaves their farm behind but finds

somewhere else to live for three years while the war rages on. It’s eventually

won and they get to go home, but Adara has lost her coldness and can’t play with

the ice lizards anymore. She also seems happier and closer to her family

instead of her only companion being an ice dragon. Her family recovers from

their ordeal and goes on to be happy.

Ice and fire, hard

winters, war, family—is it any wonder this story is frequently mistaken for

part of the Song of Ice and Fire

universe? I don’t think so.

Next week, Martin

takes on be-careful-what-you-wish-for in “In the Lost Lands.”

It's always a pleasure to read your work, Shiloh, both because the writing reads well and because it points out useful notions. I am not up enough on Martin scholarship to know if there have been treatments of rapine as a theme in his corpus, but I have to think it is a study worth doing.

ReplyDelete